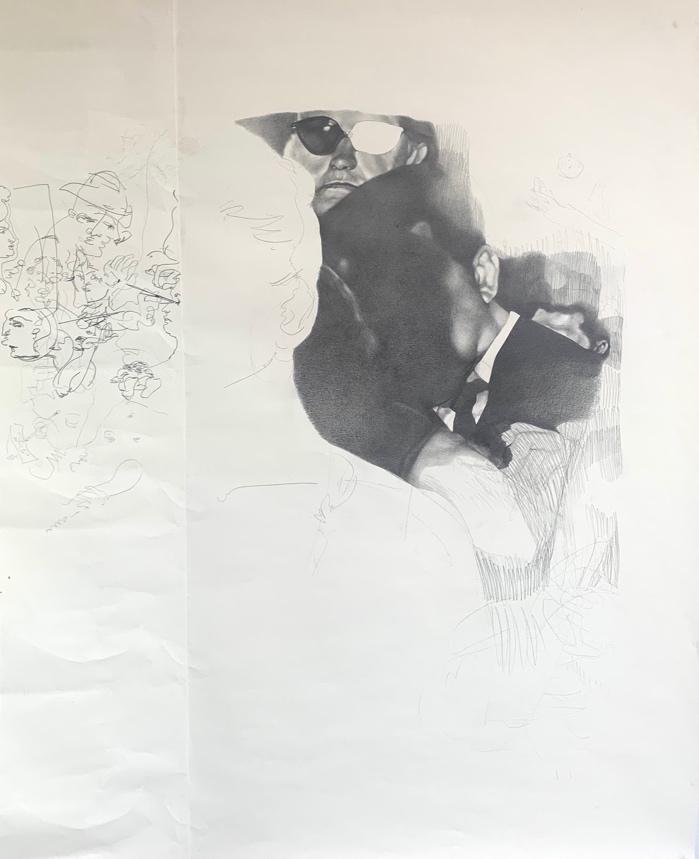

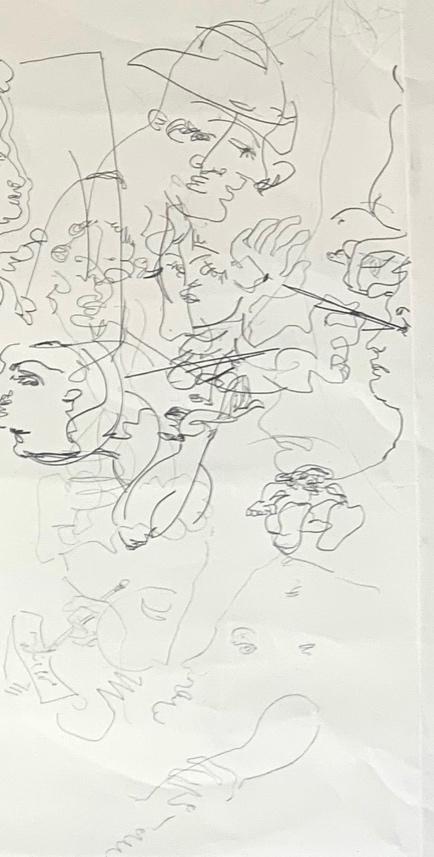

Simultaneity, by definition, implies multiples: multiple perspectives, multiple truths, and multiple modes of working all at the same time. It alludes to the idea of the synchronous, the coexistent, and the parallel—all of which weigh heavily in any interpretation of Sophia Anthony’s recent body of work. Her work—which includes the combination of painting and drawing practices—is composite; she looks to internet ephemera (YouTube screenshots, clickbait photos, paparazzi snapshots) as she compiles source imagery for each work. And although Anthony is a classically trained portraitist and learned to paint from life, these works—which include A Passenger (2021) and Lurker (2021)—are anything but portraits. Through sourcing, combining, and referencing online imagery, Anthony creates generic figures that operate as ambiguous types with surroundings that take on the quality of mise-en-scènes.

Anthony thinks a lot about painting from a screen versus from life; she thinks about the slickness of the screen, the pixelation, and the degradation of the online image. Of the images themselves, she is interested in the boundaries associated with knowing and using imagery. She asks: “How much do I know of this image? Do I find out who this person is? Do I leave that to be an unknown?” Ultimately, a guiding question remains for Anthony: “What are the boundaries of knowledge in a work?”[1] In her hands, viewers are reminded of an image’s power to both communicate and withhold information. The same goes for the artist herself as she selects her images. Anthony always questions herself as she takes inspiration: “What am I pulling from? What am I looking towards?”

At first glance, Anthony’s paintings read as normal images. Upon closer investigation, the purposefully disjointed nature of the composites become clear: the pieces don’t quite come together correctly. In creating her composite images, Anthony destabilizes the viewer’s expectations through subtle confusions. These anonymous figures are at once familiar and made strange as the rendered pieces of the composite clash against each other. In A Passenger, the viewer can’t help but question the ghostly and ambiguous hands: whose hands are these? Are they his? If so, why are they backwards? Anthony’s often uncanny rendering also extends to light and its sources. The figure depicted in Lurker is almost seen as secondary to the sharp lines of unseen reflections within the lenses of his glasses. The work seems to allude to the ghostly illumination of technology—and its hot, unnatural saturation—which overtakes the scene. Two daubs of hot orange-pink shift the temperature of the whole room; Anthony leaves nothing untouched.