Fruit exists now in multiple iterations—a carefully cut and hand-folded posterboard-packaged CD most recently. You can do Fruit at home now, like a deranged spiritual exercise tape. Fruit is a multimedia durational piece by Qiuchen (Q) Wu that might indeed best be characterized as a form of spiritual exercise—and like the Canaanites in Straub and Huillet’s stilted 1975 masterpiece Moses and Aaron, the viewer/participant remains uncertain as to what has happened to them. Is or was there a divine revelation to be had? Did I miss it by my imperfect adherence to the (religious?) discipline on offer? Maybe I’d do better to just chuck the whole thing? Why did I begin doing this at all?

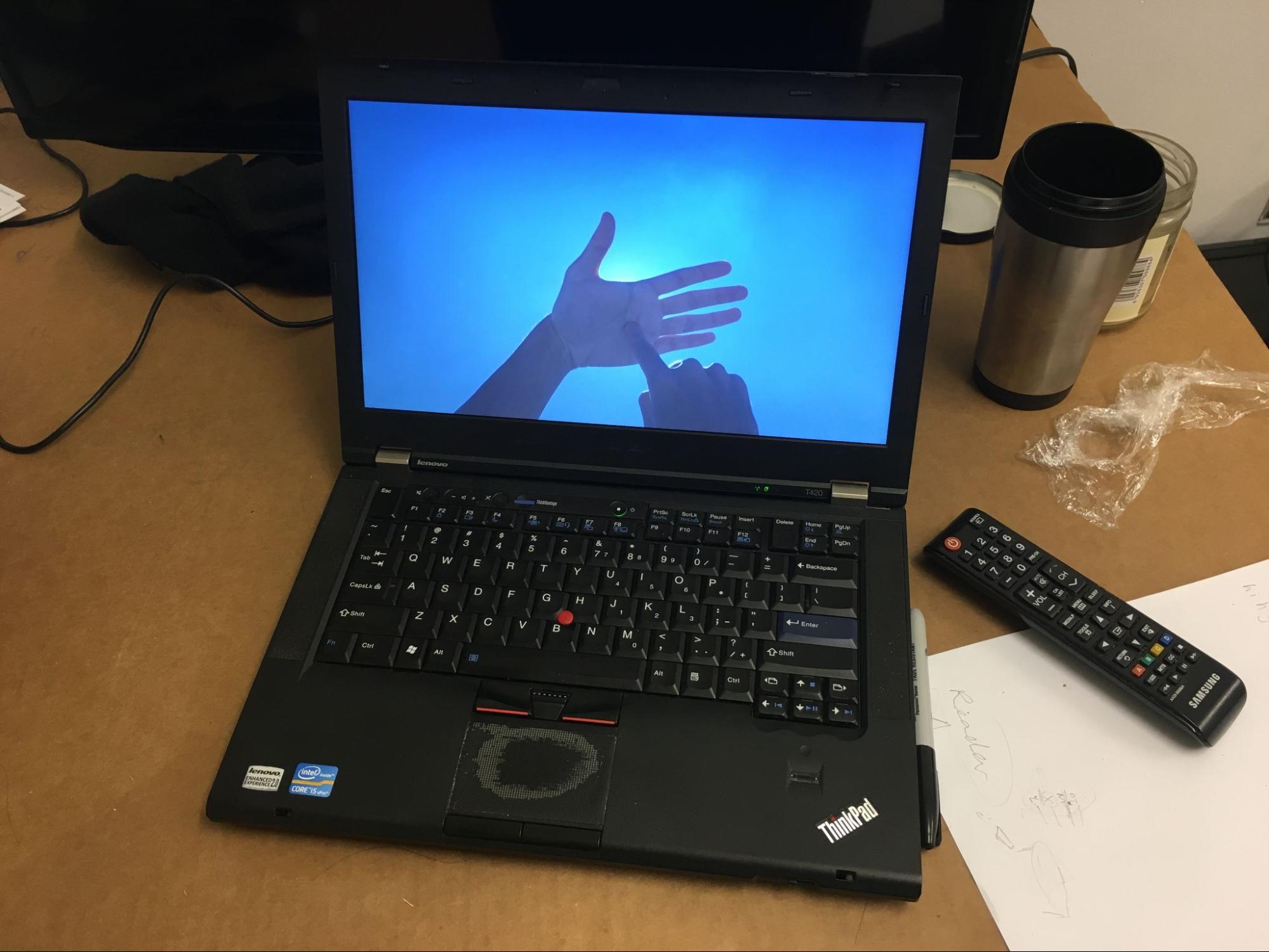

I first encountered Fruit in its installation form, in a windowless room in the gray basement of the Logan Center. A copier paper sign taped to the door with quotations from Moses Maimonides and Spinoza seemed to be trying to say something about…the inevitability of…perplexity? I wasn’t sure, and I was late, so I went in. I’d figure it out later. In the semi-dark room was a table with a bowl of apples, stacks of paper and pencils, people sitting around the periphery of the narrow space, mostly on the floor. Some of them were writing uncertainly in the dim light. Someone’s stressed-out dog was anxiously panting and whining. A video projection on what appeared to be a white bedsheet hung towards one end, providing the only illumination in the room. In the projected video a finger traced shapes onto the palm of another hand (the finger’s other hand?), nearly silhouetted against a bright blue sky (the piece appears to be shot from below). The hand appears to be blocking out the sun. After a while it became clear that the finger was tracing letters of the Roman alphabet. That was a…t, and that was….r….now…e….e. Ok, so viewers were trying to transcribe what the finger was tracing.

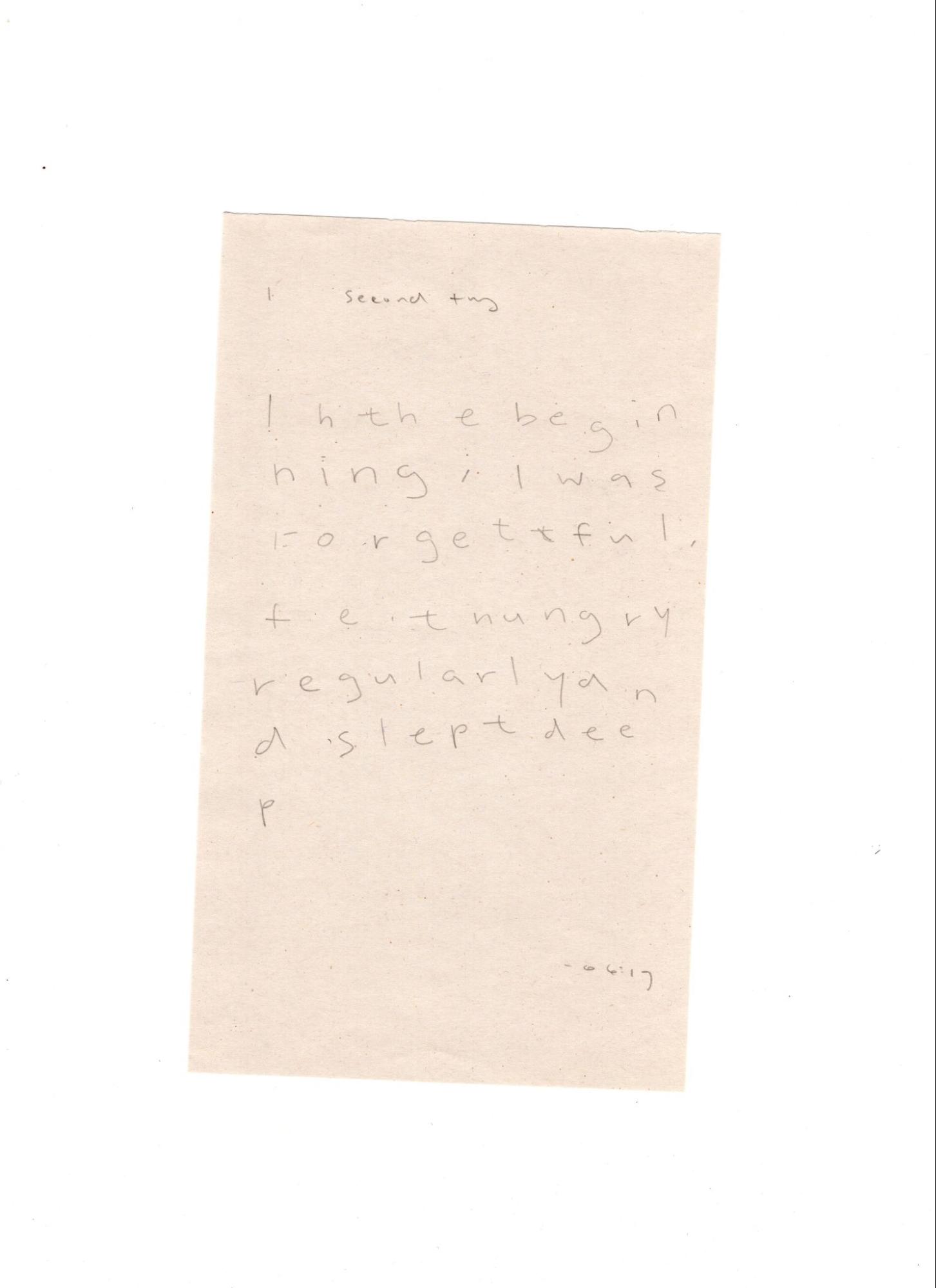

With the provided stubby, partially-sharpened pencil and copier paper I did the same, using my leg as a desk. At first it was frustrating: what an irritating exercise. Entering a little late, in mid-stream, I had no idea what I was transcribing—it quickly became clear that the text was composed of syntactically normal English sentences, and in time became vaguely legible as a narrative in the first person. There was a kind of ~antique~ quality to the language, and a folkloric or Biblical abstractness to its objects (“the fruit” “the tree”) combined with what seemed to be a generally confessional mode. An “I” was detailing its troubles in seeking…something. It was like hearing every third word in a glitchy phone call, or listening to a foreign language you partially understand. I knew the contours of what was happening, but there were holes where I missed letters or words. A lot of holes. After a while, I learned the way this particular hand made “f” and “t” and “q” and “d” and so on, and it got somewhat easier. There were flashes of recognition as the mind realized a word had been spelled out (“tree”!). But what became increasingly interesting to me phenomenologically was the state of attention the piece held me in—it was successfully forcing me to sustain my awareness in a mode at once focused and limited. I had to watch very carefully to see each letter and write it down in time. There was no time or bandwidth to have many (or any) other thoughts if I wished to catch the letters and transcribe them; almost not enough time to recognize the words as they formed. I felt myself reduced to a kind of scribe who could barely read.

The piece is long: 60 minutes [Q: the new iteration lasts 75 minutes]. I still don’t entirely know what the text said, and I felt strange and exhausted when it was over. Once I had realized what was happening, I’d decided to submit to the logic of the piece as best I could: many of the most interesting Structuralist works require this (Snow’s Wavelength or Kubelka’s Arnulf Rainer, for instance), and I’ve long appreciated works that offer a participatory structure in time, one that proposes to perhaps change my awareness of my own awareness. Fruit did that. I spent a long time in the gray and flattened uncertainty of dedicated transcription. Like the “I” of the text, I was looking for something, and I didn’t know what. At the end, I wasn’t sure where I was or what had happened to me.