When discussing his works on paper, Wilson Yerxa describes the importance of point of view. He distinguishes the point of view that his paintings and drawings inhabit from the first-person perspective, the “I” language that characterizes much of poetry.

The application of 1-, 2- and 3-point perspective in Renaissance painting became a way of organizing the world. Rather than this organization of the world cohering to a natural sense of what things were, it was used to create pictorial schemas, ordered and hierarchical space, leading the viewers’ eyes to the most important facets of the pictured scene. Thus, rather than utilizing point of view (in the sense of being an artistic tool) to foster scientific objectivity, it instead served the purpose of constructing spatialized narratives and meaning within the composition.

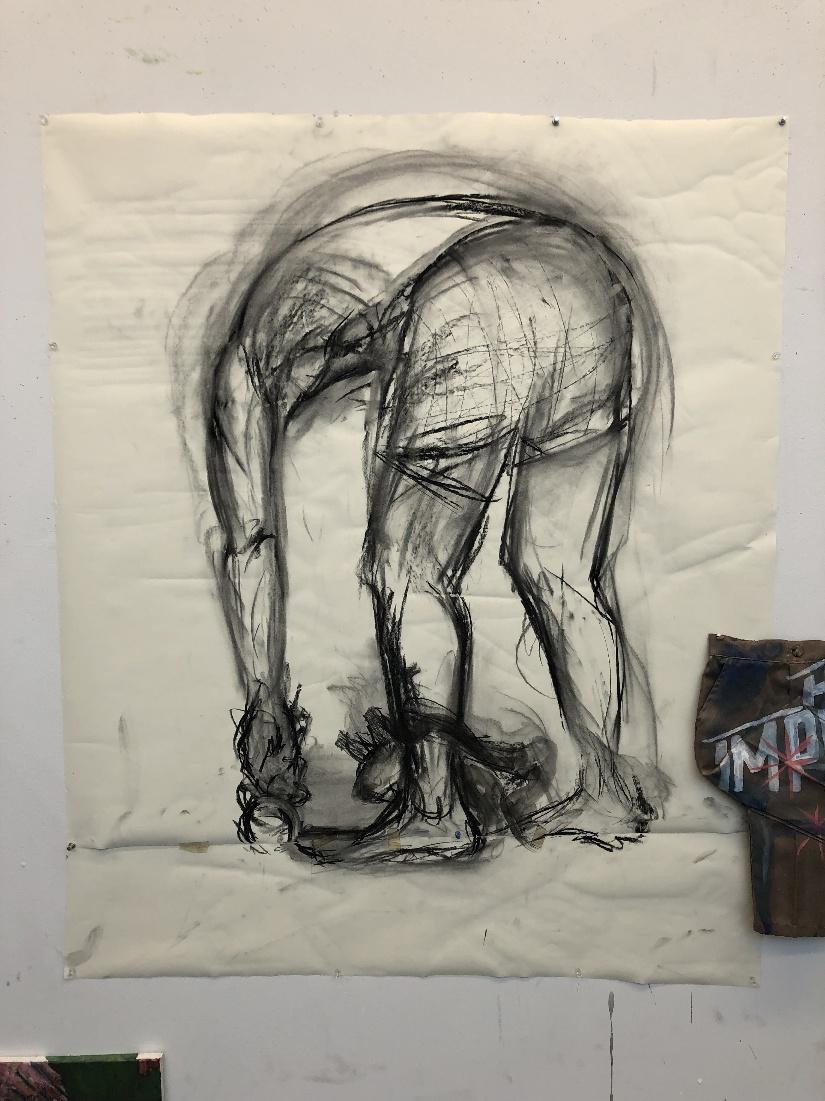

What happens, then, when instead of occupying a single point of view a painting or drawing utilizes multiple and shifting sightlines? By deploying what we might call shifting points of view and multiple lines of sight, Wilson’s work plays against the objectivity of illusory painterly representations. Take his Laptop Masturbation piece.